In Conversation: Patrick Flores, Artistic Director of the Singapore Biennale 2019-2020

Earlier this year at the Singapore Biennale we had the chance to sit down with Flores for an enlightening and insightful conversation about the role of biennales in the art world, his curatorial team and their vision for the 2019-2020 edition, questions of identity in relation to geography, and how his upbringing in the Philippines influences his practice as an art historian and curator

The Singapore Biennale curatorial team (from left to right): John Tung, Goh Sze Ying, Renan Laru-an, Patrick Flores, Andrea Fam, Anca Verona Mihuleţ and Vipash Purichanont. Image courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

Design Anthology: What role do you think the biennale plays in the art world today?

Patrick Flores: Biennales are, for me, an opportunity to gather outside of the predictable bureaucracy of institutions. There are always exhibitions happening in museums, but biennales change all the time. They change in terms of the intelligence that informs them, when a new curator comes in and offers their point of view. Unlike the bureaucracy of an institution that more or less churns out programme after programme, the biennale offers more excitement and less predictability, and possibilities for something new that can unhinge itself from the norm and the expected.

Of course, I think that the regularity and repetition of a biennale is subject to critique, but there are differences even as it repeats. It’s an iterative enterprise; a biennale is held every two years, but as it repeats it changes. Of course, it does acquire some habits that harden over time, but biennales also foster discourse about themselves, so there’s a great deal of reflexivity on the part of the curators to think about what it is they do — it’s not that they’re unaware of the critique against the model of the biennale; they enfold that awareness into the production of something different. I think the biennale is also a much-criticised platform because of its tendency to consolidate, accumulate and be an authority — because it includes, by extension it also excludes. But as it repeats, the inclusion multiplies. Every year new artists are chosen, unless the same artists are chosen over and over again, which sometimes happens. But there’s always this potential for difference within repetition.

Can you tell us about the title you gave to this edition of the biennale, Every Step in the Right Direction? What inspires you about Salud Algabre?

My field is colonial art history, and I encountered Salud Algabre in my studies of colonialism in the Philippines. I was interested in having politics inform and shape the biennale, and considered the kind of political energy it should convey to the public.

The title Every Step in the Right Direction is a line from an interview that Algabre once gave. It offers this delicate balance between urgency and hope, and I like that the two are embedded in one line. Algabre was a seamstress who joined the movement against the Americans and wasn’t very successful in seizing authority from the colonial powers. But when she was interviewed years later — the uprising took place in the 30s and she was interviewed in the 60s — she was quick to correct the interviewer when they asked her, ‘Where did you go after the revolution failed?’ She said, ‘No uprising fails. Each one is a step in the right direction’. So again, I liked that balance between urgency and patience, and sustainability and this foil for heroic gestures that usually leads to fatigue and exhaustion. I wanted this biennale to offer sustainable gestures. We are in a long-term struggle for change but it doesn't happen quickly or easily. Our bodies are finite and fragile, so we have to be more forgiving and less hard on ourselves, but at the same time quite resolute too, in a sustained way. I consider it an achievement to be able to take a title from this historical figure in the Philippines — who was active almost a hundred years ago — and make her reflection resonate with contemporary art practise.

What influence does your upbringing in the Philippines, and your country's own art scene, have on your perspective as a curator?

It's a unique situation, there’s a great deal of mixture. The Philippines is one of few countries in the world that’s been colonised three times. That kind of mixture shapes a different mindset and intelligence. It shapes a critical relationship with the outside and the foreign, but also an ability to translate the foreign and integrate or rearticulate it into local culture. I think that dynamic is important for me, that the outside isn’t feared but rather mediated in a critical and creative way. Aside from the intense mixture as a result of colonialism, there’s also mass migration — Filipinos are all over the world doing all sorts of things, mainly in the fields of effective labour like care-giving, entertainment, art and design, and that’s also an interesting phenomenon. I think this shaped me into a productive curator in a sense, because the culture isn’t monolithic, it's one of mixture, but because of this there’s still always an anxiety about originality or authenticity.

In discussions about Southeast Asia, the Philippines usually falls off the map because it doesn’t have a great tradition in comparison to say India or China. We don’t have large monuments like Borobudur or Angkor Wat. But maybe that’s a blessing in a way, to not be governed so much by a civilisational discourse but rather by a practise of constantly translating things that supposedly come from the outside or are considered foreign. Curatorial work is largely translation and it requires sympathy for the things that you don’t know or like, or that confuse you. So, for me this cultural make-up feeds into a particular curatorial imagination.

What do you think it means to ‘confront and reconsider the ideas and values that have come to embody “Asian” identity’?

That’s a tough one. Identity is a kind of a rigid expectation. What contemporary art and contemporary curatorship can do is dissolve that rigidity by opening up possibilities of subjectivity that don’t necessarily adhere to one identity. The self is complex. It's usually reduced to identity by certain interests that want to capture the individual for a range of reasons. Nation states exploit identity; capitalism exploits identity. But if we open up the self to many subjectivities then it’s less prone to these efforts to instrumentalise or reduce to a particular recognisable form of identity. I stay away from the word ‘identity’ because I think it reduces the complexity of the self. And then you have the notion of ‘Asian’, which is of course also a simplification of the complex geographies and encounters between people within these regions.

Talking specifically about Southeast Asia is also a problem, and that’s what the Singapore Biennale wants to reflect on. The focus of the Biennale is Southeast Asia, and a considerable number of the artists included come from the region, but the curators and I wanted to unhinge or unburden Southeast Asia from its geopolitical construction, which is of course an inheritance or legacy of colonialism. It's not that it’s entirely meaningless, but I don’t think it can govern the possibilities of this location, Southeast Asia. So we wanted to rethink that and offer a critique of the construction of Southeast Asia, but at the same time connect to a larger world through the region — and one way to do that was for us to look at the waters that surround Southeast Asia, the Pacific, the South China sea and the Indian Ocean. These waters surround the region and at the same time connect it to a wider context. We wanted to include artists from outside the region within a framework rather than just randomly, and one of these frameworks was to look at the surrounding waters and see where the region may be connected. So, in a way geography is remapped through contemporary art. The existing cartography is overwhelmingly governed by geopolitics, but with the biennale we’re saying that contemporary art can offer a different mapping of our place in the world.

What role do you think Singapore plays within the regional art community?

Singapore has both modern and contemporary art institutions that want to consolidate material through collection-building, exhibition-making and the formation of discourse through research, symposia, conferences, publications and archiving. That’s their agenda, to consolidate the materials that pertain to the art of the region. They’re in the position to do that because of their financial resources, and the biennale is part of that consolidating, to consolidate a position in the world of biennales and to be able to locate the region in the context of a global conversation about art. So one can say Singapore is a leader in the region when it comes to consolidation. But you can also see that the institutions are hospitable to non-Singaporeans. They seek to attract talent from around the region to come and work in Singapore. It has its positives and negatives. The downsides are that other parts of the region may lose talent, but of course the upshot is that the discourse becomes enriched by a wider range of expertise, experience, talent and intelligence. I think that's the role of Singapore plays.

Consolidation comes with implications. I think one way we can use this tendency to accumulate, amass, consolidate and establish authority is to share the opportunity to produce knowledge, exhibitions and discourse, and to disseminate that across the region so that the consolidated knowledge doesn’t just stay here but actually moves around. So there should be strategies to make this happen, like more inter-institutional collaborations to foster conditions of growth, otherwise you get a concentration in one place, which isn’t really productive.

How and why did the curatorial team become six in total? How was that decision made and what did each of the curators bring to the broader vision?

I wanted to work with and learn from young curators. I wanted some sort of intergenerational relationship. I was trained as an art historian, so my curatorial practise is an extension of my work in that field. At that time, there was no institution in the region that formalised curatorial training, so even earlier than my time it was the artist who curated. There was this figure of the artist-curator, and later it was the art critic or the art historian who extended their practise to encompass curatorial work, but at some point in the late 90s or early 2000s, because of the emergence of curatorial professionalisation overseas, the landscape changed and so we now have curators who studied curatorship, which was unknown before. My generation had a more idiosyncratic, improvisational approach to curating, one that relied on what we do, whether we were artists or art historians, and we just learned as we did it. But now there’s this formalisation, professionalism and specialisation, so I think the mindset has changed and I want to learn from this generation of curators.

Also, these curators are no longer exclusively interested in exhibition-making as the main expression or articulation of curatorial work. In an earlier time, curatorial work meant custodianship, keeping objects, making sure they are well looked after and preserved. At some point curatorial work came to largely mean exhibition-making and making art accessible to the public, but the contemporary context has changed and the expectation of curatorial work also means activating objects in space and creating conditions for more dynamic interaction between the public and artwork in a range of ways.

A great deal of this articulation happens within the exhibition space, so the exhibition is not a fully formed thing, it’s subject to remaking and re-articulation between the public and the artist. The curators I selected for this edition of the biennale are interested in that, and in that kind of curatorial work. I wanted to bring onboard curators who are invested in research, not only as preparation for selection, but as a methodology of presenting work in the space. I also looked at the geographies that interested them. Renan Laru-an is from the Philippines, but from the south; Goh Sze Ying was based in Kuala Lumpur before moving to Singapore; Anca Verona Mihuleţ is Romanian but lives in Seoul; Vipash Purichanont lives in Bangkok and is interested in northern Thailand and how it spreads out into India and that area; Singaporean John Tung is interested in the Austronesian movement of the early people of Southeast Asia going from China into Taiwan, then to the Philippines, the South Pacific, and eventually all the way to Madagascar. So, I really looked into the interests of the curators in terms of geography — in both physical location as well as their areas of research.

Biennales have a reputation for being quite academic and dense, were you and the curatorial team conscious of making it more accessible for the general public?

That’s always an anxiety among curators. The world is very complex and contemporary art has become complex, too. Curators, independent of contemporary art curation, have their own discourse about what it means to curate, what the relationship is between curatorial work and political life, and social content — so a biennale is a very layered project. For this particular biennale, I wanted it to be an intersection between a seminar and a festival, so I didn't want it to be too dense or too obscure and only appeal to the art world echo chamber, because that’s what the art world can be, an echo chamber. But at the same time, we have to acknowledge the complexity of the world that contemporary art responds to and the equally complex language in which it responds. We wanted to achieve a delicate rhythm that alternates between a seminar and a festival.

As told to / Suzy Annetta

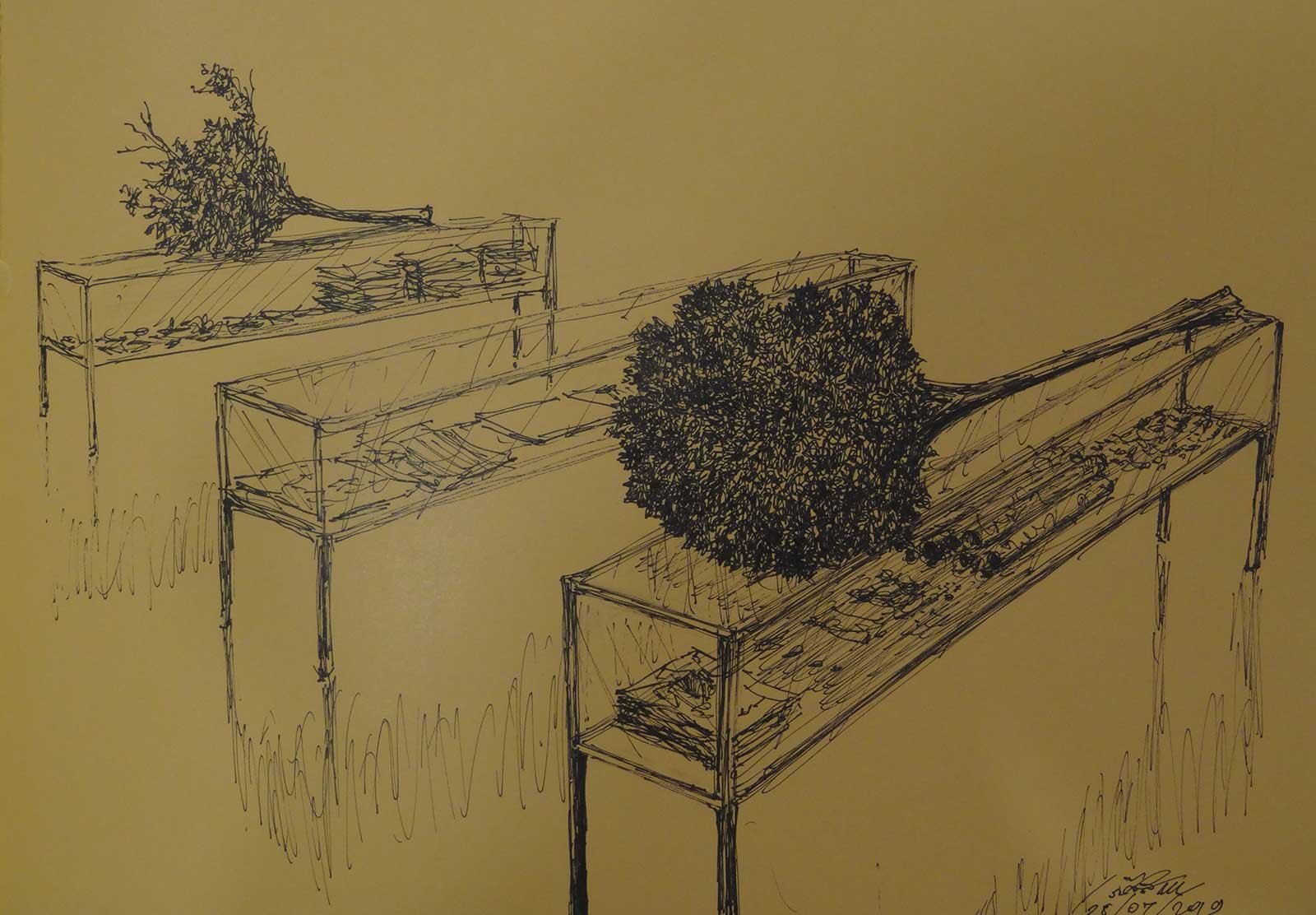

Ruangsak Anuwatwimon, Reincarnations (Hopea Sangal and Sindora Wallichii), artist impression. Image courtesy of the artist

Min Thein Sung, Time Dust (details). Image by Aung Is Thu Hlaing, courtesy of the artist

Min Thein Sung, Time Dust (details). Image by Aung Is Thu Hlaing, courtesy of the artist

Le Quang Ha, Slaughter House from Gilded Age. Image by Nguyen Nam Hai, courtesy of the artist

Kahlil Robert Irving, Many Grounds (Many Myths), from the Many Grounds (Many Myths) series. Image by Jackie Furtado, courtesy of the artist and Callicoon Fine Arts, New York

Dusadee Huntrakul, The Map for the Soul to Return to the Body. Image courtesy of the artist and BANGKOK CITYCITY GALLERY

Sharon Chin, Composition for a Monument (artist sketch for In the Skin of a Tiger). Image courtesy of the artist

Mathias Kauage, Marbles. Image courtesy of Andrew Baker Art Dealer, Brisbane

Hera Büyüktaşçıyan, A Study on Endless Archipelagos (detail). Image courtesy of the artist